This standalone post is not a part of the Dead God project, just a little piece of content. I wanted you to read the excerpts.

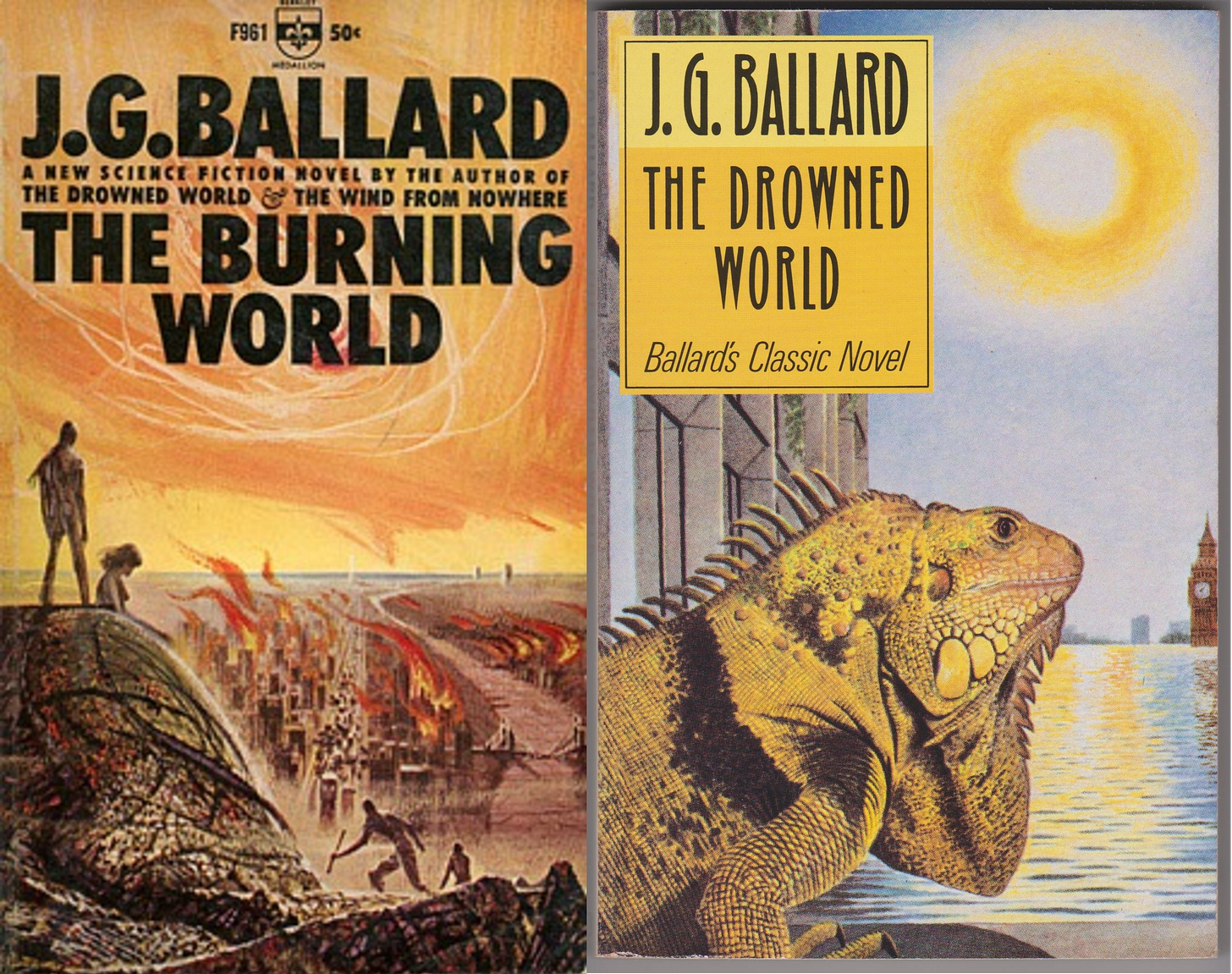

The Drowned World, J.G. Ballard. First published 1962.

The Drought, J.G. Ballard. First published as The Burned World in 1964, then expanded and republished with its final title in 1965.

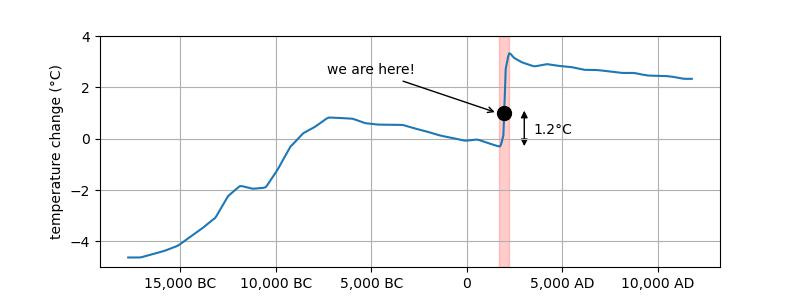

The earth stasis of the Holocene is rapidly unraveling and throwing the world into a chaotic change. Systems thinking (cybernetics) implies that at some point a new stasis will be reached, at a higher enthalpic level:

The location—on both the x and the y—of the peak which ends the interlude of rapid change can only be an object of speculation at this point. As far as I understand it, the peak means we have stopped or drastically decreased burning fuel. Why that would happen is not clear. Unless as the world warms it somehow releases a countervailing mechanism, like a volcanic winter, but that’s not on this graph. Will we stop burning fuel because there will be fewer of us around to burn it? Because we’ve run out? Because there won’t be anyone alive to do anything? Or will it be because we had a revolution?

However, the third world that follows, that long line into the future, optimistically sloping downward, is more predictable. The earth has been that hot before, 65 million years ago. The seas will be much larger, and they will be less able to distribute heat and water around the globe. The wet spots will get wetter, the dry spots will get drier, and there will be no more icy spots.

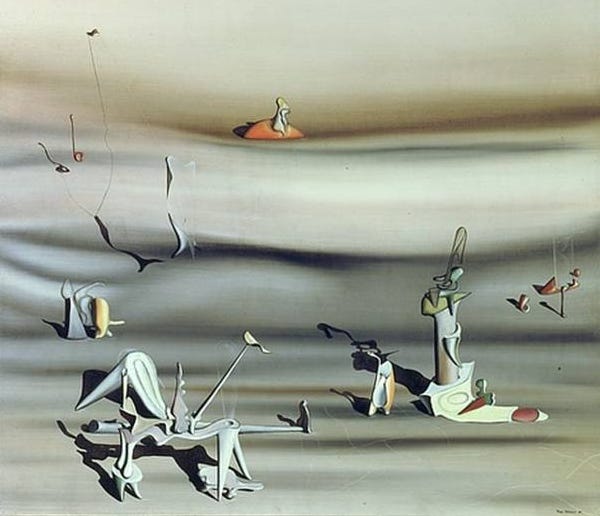

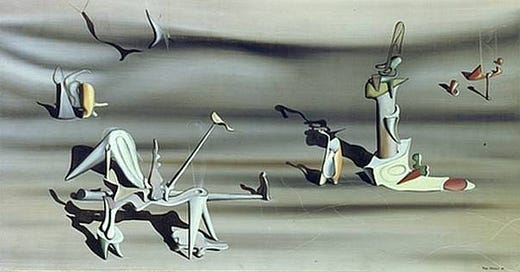

If we want to imagine that world, we can do no better than JG Ballard, particularly his two climate novels—a subset of his disaster novels—The Drowned World and The Drought, originally published as The Burned World.

The two worlds of these novels together describe the world we are growing into by flooding the atmosphere with carbon. In each, a climate change is the main driver of the narrative. In each, the effects—not the causes—parallel and foretell the change we are now living through. This works well because in all of Ballard, the reader can get the feeling that the narrative is just an interruptions of the landscape descriptions, the mood setting that the author is truly interested in creating. Ballard writing is atmospheric, thoroughly.

In The Drowned World the sun is getting hotter, so the earth is getting hotter. In the world of The Drought, by a chance quirk of chemistry that luckily didn’t turn out to be true, plastic polymers and petroleum-based industrial waste dissolve in the ocean, then float to the top, and there forms new bonds forming a plastic film over the ocean that prevents all evaporation. Rain ceases and the rivers and lakes begin their last final march into the sea.1

One of the reasons I like Ballard so much is that he breaks down any vestigial remnant of the separation between human and animal. There’s a long tradition of people wondering what separates the two categories — is it our toolmaking? Language? Prehensile thumb? But that very effort reveals a deeper truth: humans are animals, first and foremost. By placing his characters at the mercy of their climate, Ballard animalizes us.

This is most explicit in The Drowned World, in which the actors have been left behind by the rest of humanity, living in the ruins of flooded cities that have been emptied almost completely, the high-rises and hotels retreating into the water, their upper floors becoming vertical jungles. The world as a whole is moving backward in time, back to the hot world of the dinosaurs. It begins like this,

Soon it would be too hot. Looking out from the hotel balcony shortly after eight o'clock, Kerans watched the sun rise behind the dense groves of giant gymnosperms crowding over the roofs of the abandoned department stores four hundred yards away on the east side of the lagoon. Even through the massive olive-green fronds the relentless power of the sun was plainly tangible. The blunt refracted rays drummed against his bare chest and shoulders, drawing out the first sweat, and he put on a pair of heavy sunglasses to protect his eyes. The solar disc was no longer a well-defined sphere, but a wide expanding ellipse that fanned out across the eastern horizon like a colossal fire-ball, its reflection turning the dead leaden surface of the lagoon into a brilliant copper shield. By noon, less than four hours away, the water would seem to burn.

…

A giant Anopheles mosquito, the size of a dragon-fly, spat through the air past his face, then dived down towards the floating jetty where Kerans' catamaran was moored. The sun was still hidden behind the vegetation on the eastern side of the lagoon, but the mounting heat was bringing the huge vicious insects out of their lairs all over the moss-covered surface of the hotel. Kerans was reluctant to leave the balcony and retreat behind the wiremesh enclosure. In the early morning light a strange mournful beauty hung over the lagoon; the sombre green-black fronds of the gymnosperms, intruders from the Triassic past, and the half-submerged white-faced buildings of the 20th century still reflected together in the dark mirror of the water, the two interlocking worlds apparently suspended at some junction in time, the illusion momentarily broken when a giant water spider cleft the oily surface a hundred yards away.

Continuing into dinosaur territory:

All the way down the creek, perched in the windows of the office blocks and department stores, the iguanas watched them go past, their hard frozen heads jerking stiffly. They launched themselves into the wake of the cutter, snapping at the insects dislodged from the air-weed and rotting logs, then swam through the windows and clambered up the staircases to their former vantage points, piled three deep across each other. Without the reptiles, the lagoons and the creeks of office blocks half-submerged in the immense heat would have had a strange dream-like beauty, but the iguanas and basilisks brought the fantasy down to earth. As their seats in the one-time boardrooms indicated, the reptiles had taken over the city. Once again they were the dominant form of life.

Looking up at the ancient impassive faces, Kerans could understand the curious fear they roused, rekindling archaic memories of the terrifying jungles of the Paleocene, when the reptiles had gone down before the emergent mammals, and sense the implacable hatred one zoological class feels towards another that usurps it.

Kerans is from one of the new cities of the arctic circle, but Dr. Bodkin remembers the city from its dry-land heyday. But his city is below him, and the landscape is alien and strange even for the good doctor, who offers this theory:

“Is it only the external' landscape which is altering? How often recently most of us have had the feeling of deja vu, of having seen all this before, in fact of remembering these swamps and lagoons all too well. However selective the conscious mind may be, most biological memories are unpleasant ones, echoes of danger and terror. Nothing endures for so long as fear. Everywhere in nature one sees evidence of innate releasing mechanisms literally millions of years old, which have lain dormant through thousands of generations but retained their power undiminished. The field-rat's inherited image of the hawk's silhouette is the classic example—even a paper silhouette drawn across a cage sends it rushing frantically for cover. And how else can you explain the universal but completely groundless loathing of the spider, only one species of which has ever been known to sting? Or the equally surprising—in view of their comparative rarity—hatred of snakes and reptiles? Simply because we all carry within us a submerged memory of the time when the giant spiders were lethal, and when the reptiles were the planet's dominant life form."

Feeling the brass compass which weighed down his pocket, Kerans said: "So you're frightened that the increased temperature and radiation are alerting similar IRM's in our own minds?"

"Not in our minds, Robert. These are the oldest memories on Earth, the time-codes carried in every chromosome and gene. Every step we've taken in our evolution is a milestone inscribed with organic memories—from the enzymes controlling the carbon dioxide cycle to the organisation of the brachial plexus and the nerve pathways of the Pyramid cells in the mid-brain, each is a record of a thousand decisions taken in the face of a sudden physico-chemical crisis. Just as psychoanalysis reconstructs the original traumatic situation in order to release the repressed material, so we are now being plunged back into the archaeopsychic past, uncovering the ancient taboos and drives that have been dormant for epochs. The brief span of an individual life is misleading. Each one of us is as old as the entire biological kingdom, and our bloodstreams are tributaries of the great sea of its total memory. The uterine odyssey of the growing foetus recapitulates the entire evolutionary past, and its central nervous system is coded time scale, each nexus of neurones and each spinal level marking a symbolic station, a unit of neuronic time.

"The further down the CNS you move, from the hind-brain through the medulla into the spinal cord, the further you descend back into the neuronic past. For example, the junction between the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, between T-12 and L-1, is the great zone of transit between the gill-breathing fish and the airbreathing amphibians with their respiratory rib-cages, the very junction where we stand now on the shores of this lagoon, between the Paleozoic and Triassic Eras."

Bodkin went on: "If you like, you could call this the Psychology of Total Equivalents—let's say 'Neuronics' for short—and dismiss it as metabiological fantasy. However, I am convinced that as we move back through geophysical time so we re-enter the amnionic corridor and move back through spinal and archaeopsychic time, recollecting in our unconscious minds the landscapes of each epoch, each with a distinct geological terrain, its own unique flora and fauna, as recognisable to anyone else as they would be to a traveller in a Wellsian time machine. Except that this is no scenic railway, but a total re-orientation of the personality. If we let these buried phantoms master us as they re-appear we'll be swept back helplessly in the flood-tide like pieces of flotsam."

I don’t think this neuronic devolution should be dismissed out of hand by inhabitants of 2025. Who could deny that politics gets stupider as it gets warmer? Ballard’s inhabitants, one wants to call them, are not affected by Trumpian fascists, but are alone. There are four or five of them in the whole grotto of the novel. Most have fled or died. They are living the lives of scavenger animals, scavenging for meaning among the inert baking ruins of a city that was built on ground that is now seafloor. We are living in a densely populated iconosphere of brain rot in a warming world, because the warmening is happening faster and in a less orderly way than anyone, even Ballard, could have accounted for.

The main character of The Drought is a divorced doctor in the fictional city of Hamilton, which sits upriver from the coast. Upon his separation from his wife, he impulsively buys a houseboat on the waterway. The houseboat was probably cheap because the Drought, driven by the film over the ocean, had already begun. Like all waterways, a culture had grown up around the lake and the river; people make their livelihoods on the water, and other people, like our doctor, end up there when they have no more reason to be on land. As the water dries up, that culture becomes desiccated and the relationships between the inhabitants becomes strained, as each deals with the stress and change in their own way. They’re all watching each other to see who’s going to be first to leave for the Coast. Absent the water that brought them together, some become anti-social; the fishermen form a gang that abducts people along the water front. The early stages of drought bring fires in the city that burn unchecked.

As weather systems stagnate, driving each climate zone into extremes, we will be coping with drought and desertification in places unused to it. It could rain in the Sahara but turn the Pantanal into a desert. How human behavior changes in the context of its climate will have to be discovered. “Is it only the external landscape which is altering?” Or do our minds, personalities, and cultures change, fragment, and retreat as the world changes?

Those captains of industry pioneering the practice of dumping waste into our oceans couldn’t know that wouldn’t happen. That kind of thing could have happened; maybe it would have been better if it had — maybe an acute crisis would have been more solvable than the drawn-out one.

Also like JG Ballard’s work.