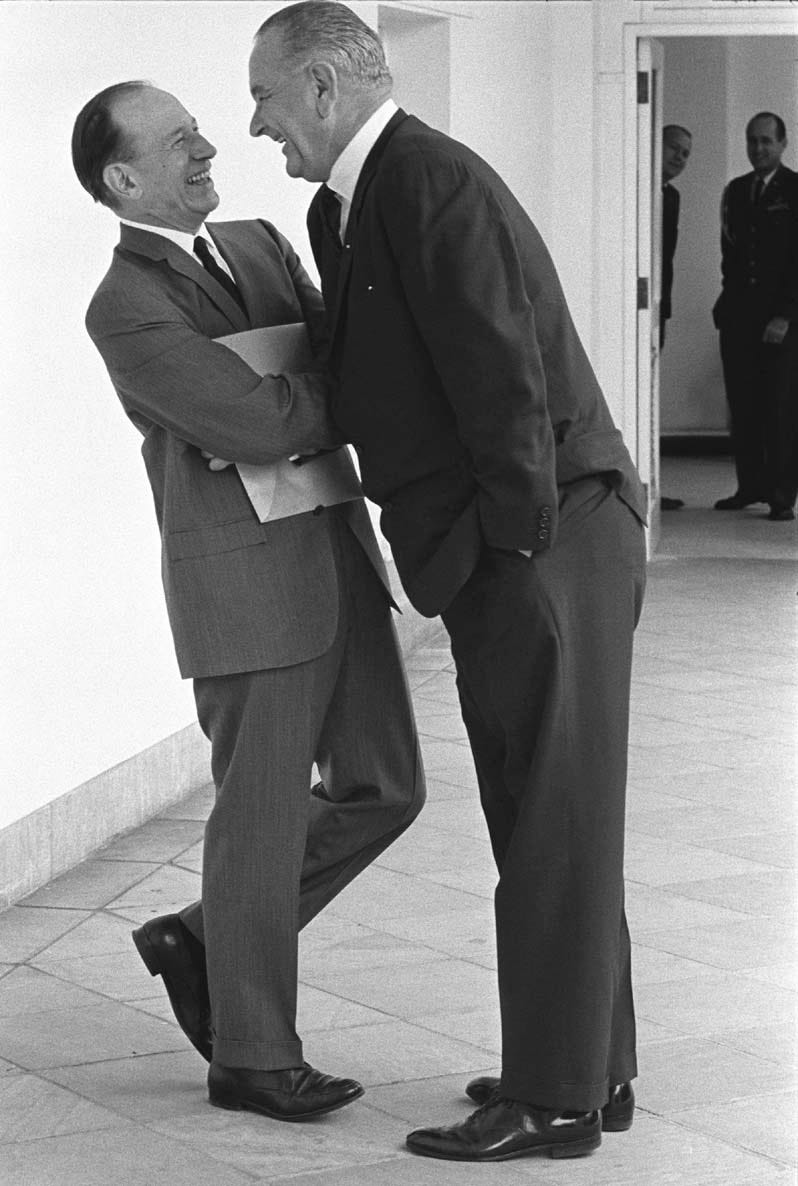

LBJ

JFK part 1 of 2

This is only about oil when placed in the context my 112,321 word document I’m working on. So read on for my JFK takes.

Lyndon B Johnson was not an emotionally healthy man. This was what made him interesting to Robert Caro and many of his other biographers. He was severely bipolar, subject to manic periods and depressions. The mania could manifest as rage, or as a compulsive ambition. There may well have been some obsessive-compulsive disorder in his psychic stew.

According to psychiatrist Dr Bertam S. Brown, who had seen a number of presidents including Johnson, “Johnson’s humiliation of his employees was a way of exercising his power … Johnson was a megalomaniac … He was a man of such narcissism that he thought he could do anything.”

He was obsessive about becoming the President of the United States. Robert Caro describes a scene when a twelve-year-old Lyndon Johnson announced to his playmates, “Someday, I’m going to be president of the United States.” The other children said they wouldn’t vote for him and he replied, “I won’t need your votes.”1 Maybe he wasn’t very likeable. After all, as a kid he tortured and killed a mule, and set of explosives in the town square.2

Ed Clark, probably the man who shared the most prostitutes with Lyndon,3 said he “was an emotional man, and he could start talking about something and convince himself it was right, and get all worked up, all worked up and emotional, and work all day and all night, and sacrifice, and say, ‘Follow me for the cause!’—‘Let’s do this because it’s right!’”

He was serious about being the president. Texas State Senator Charles Herring, for instance, reported that Johnson said, “I’m going to be President. I was meant to be President. I was intended to be President. And I’m going to be.”4

And yet he lived “his utter fear of the agony of ego-crushing rejection caused him to refuse to enter political campaigning.”5 He didn’t like asking for people’s approval. Every election run, he’d “gotten himself into such an anxious and stressful state that he became physically ill as election day neared.” Ed Clark felt the same way, saying frequently, “Don’t believe in elections. Not for me.” They were big, costly gambles; for the investment to be made, it had to be a sure thing. Bobby Baker, his operative in the Senate days, said Johnson “had a deep fear of being defeated. He always was petrified by that notion.” He was “haunted by fears of failure.”6

And yet again, he was addicted to success, and absolutely driven towards his single goal: John Connally said to Horace Busby that Lyndon “says he never has another thought, another waking thought except to lust after the office” of President.7 The only path to that office was through massive corruption, promising capitalists wild returns upon their investment in him. And he knew how to do it. His most Texan biographer, J. Evetts Haley,8 said he “took to the techniques of influence and pressure like a kitten to a warm brick.”9

The Cowboy Congressman Richard Kleberg had just gotten elected representative of San Antonio, Lyndon’s home town, and needed a secretary. It was in this capacity that Lyndon traveled to Washington the first time, in 1931. Keberg was a rich kid—raised on his dad’s massive ranch—who just wanted to spend his in Washington on luxury and fun, and not work. Lyndon ran his office entirely, from casework to policymaking. He was known to impersonate Keberg on the phone. He subsequently ran for Keberg’s office and won—the cleanest election he won in his career, not to say it was spotless.

Meanwhile, Lyndon had fallen into a homosocial and political relationship with Ed Clark, who was secretary to Governor Allred. That is to say, Ed Clark became Lyndon’s attorney, with all the privileges and confidentialities that implied. For Clark, “the bond from sharing a prostitute was a means of gaining a man’s allegiance. Having done something immoral and illegal, particularly by the standards then in effect, with neither participant able to tell on the other, like schoolboys sharing a naughty little secret….He and Johnson found that common bond, they ‘shared a whore.’”[12] They used this tactic, known as sexual blackmail, to expand their web of influence widely in the State Capital of Texas. “The abuse practiced by these men in power was clear at all levels. Blacks had no chance. The Klan or men with its racist attitudes were always ready to 'defend’ themselves from the former slaves and keep them ‘in their place.’ Women were similarly mistreated, both as wives and as employees…. For many, unwanted sex was simply a part of the job, and that so-called right for the men was regularly abused by Johnson and Clark…. Catholics and Jews were treated prejudicially and were excluded from the ‘good old boys’ club[s]. The only ‘right’ was with white Protestant men. Finally, the poor were largely ignored, suffering the abuse made possible in a system run by men in power like Johnson and Clark. The finishing touch was in politics. There were no Republicans. Texas was a one-party state.”[13] After Clark went into business as an attorney, the two cooked up sophisticated schemes around New Deal projects, and so became enmeshed with a construction company, Brown & Root.

He lied about his military service during World War II in extravagant detail; he had been an observer of a single bombing run that lasted thirteen minutes, and somehow he earned a Silver Star medal, and he commissioned authors to write a pop book based on his false account. LBJ’s other biographer, Robert Dallek, concluded that General MacArthur had awarded the medal in exchange for a pledge that he would lobby FDR for more resources in the pacific theater.[14]

In 1941, oilmen Charles March, Sid Richardson, and Herman Brown offered Lyndon a free stake in an oil company that would have been worth approximately three quarters of a million dollars. This time he turned it down, saying he couldn’t be a successful politician if he was considered to be an “oilman.”[15] He has money coming in through Brown & Root, who would give their employees bonuses and then force them to donate exactly the amount of that bonus to Johnson. That year he lost his first Senate election.

In 1948, he ran for Senator again. The primary campaign, which was the only one that mattered since Texas was a one-party Democratic state, was against Coke Robert Stevenson, named after the former confederate Governor of Texas Richard Coke.[16]

Ed Clark ran the campaign off of large amounts of cash delivered by the oilmen, but also took out a huge amount of debt, knowing that it would be easy to pay off if Lyndon won, and impossible if not. “Success or suicide."[17] The folk wisdom about Lyndon’s platform was “Johnson’s friends were for [The New Deal], and Johnson’s friends were against it. Johnson supported his friends.”[18] This was not overwhelmingly popular among the regular people, not being Johnson’s friends.

At that time in Texas politics, votes could be bought, but it was expensive. It was a matter of buying the precinct chairman, and he would manually cast the votes needed. By a week before the election, Clark thought he had the majority of precincts wrapped up, but needed counties “in what was then known as Parr Country,” south of San Antonio, right up against Mexico. This borderland was run by George Parr, known as the Duke of Duval, who “got a share of the profits not only from gambling and prostitution, but even from the sales of alcohol in Duval County, receiving a nickel from every bottle of beer sold.” During the 1948 election, Parr was both county judge and sheriff in Duval County.[19] Caro writes, “The Parrs had ruled Duval County since 1912, when Archie sided with the Mexicans after an ‘Election Day Massacre’ in San Diego, the county seat, that left three Mexicans dead.” Maybe a reader can find out how an event in San Diego lead to the feudal control of Duval County and let me know, Caro doesn’t explain it.

One local radio commentator, Bill Mason, criticized Parr and his feudal control of Duval County. After the election, Parr had a deputy Sheriff, Sam Smithwick, murder Mason. Smithwick went to jail and stayed there, for the time being.[20]

On election night, Lyndon trailed his opponent, Coke Stevenson, by 854 votes. Over the next two days, more results were reported, and the difference shrank, but not enough. On George Parr’s authority, Ed Clark sent his employee, Donald Thomas, to Alice, Texas, the poorest Mexican district and the county seat of Jim Wells County, where the precinct captain was Luis Salas, who said he was “the right hand of George B. Parr in Jim Wells County [for]ten years of violence, crime and killings due to the ambition of crooked politicians.”[21] Salas refused to write the fraudulent votes themselves. Thomas sat down and did the work of making up fake names and filling out ballots. He filled 202 ballots, 200 for Lyndon and 2 for his opponent, Stevenson, who quickly challenged the results. It took all night. [22] Don Thomas stayed in Alice, to remove and destroy the fraudulent ballots afterwards. Coke challenged the fraudulent results in court.

The legal team was waiting. Ed Clark had a criminal defense lawyer at his firm named John Cofer, who took this case. But most importantly, Clark called future-supreme-court justice Abe Fortas, who happened to be in Dallas. Fortas made an illegal call (McClellan, a lawyer, emphasizes this) to Justice Hugo Black: “When Fortas called Black, he did not just request a hearing as it has sometimes been reported. He ran the entire case by Black verbally, discussing with him its nature and merits. He also discussed other activities such as getting together socially. He also emphasized the importance of Johnson being in the Senate as a Democrat and a liberal. Fortas made other arguments involving national politics that were irrelevant to the election challenge, but important to Black. In short, Fortas relied on politics, friendship, and benefits to make his case. Stevenson and his lawyers never heard the discussions and were never allowed to respond to all these secret inducements. They were denied even the chance to get a fair hearing.”[23]

And so, Lyndon went to the senate, and then became senate majority leader and Master of the Senate. All you need to know without reading three volumes of character description and limited hangout.

My footnotes got all tangled in the conversion from word, sorry.

Qtd. In Philip F Nelson, LBJ: The Mastermind of the JFK Assassination. New York: Skyhorse, 2011. chapter 3.

Robert Caro, The Path to Power, pg 100.

Barr McClellan, Blood, Money & Power: How LBJ Killed JFK. New York: Skyhorse, 2011 pg 34.

ibid.

Caro, Master of the Senate, Chapter 5

Caro, The Passage of Power, Chapter 1, ctrl+f Herring

Nelson cites Hershman, D. Jablow. Power Beyond Reason: The Mental Collapse of Lyndon Johnson. Fort Lee, NJ: Barricade Books, 2002. 104-105. That’s a quote from Nelson.

Horace Busby, recorded interview by Sheldon H. Stern, Mary 26, 1982, (p. 4), John F. Kennedy Library Oral History Program.

Caro, Passage of Power ch 1

[10] It’s a good thing, when applied to J. Evetts Haley. Underappreciated writer.

[11] Haley, 11

[12] McClellan 48.

[13] McClellan 48-49. If you use it.

[14] Nelson, LBJ quotes an interview with Robert Caro and Robert Dallack on CNN: The Story of LBJ’s Silver Star, by Jamie McIntyre (CNN military affairs correspondent) and Jim Barnett (CNN producer)

[15] Caro, Master of the Senate, pg 111

[16] Caro, Means of Ascent, Chapter 8, ctrl+f Richard Coke

[17] McClellen Chapter 6

[18] ibid

[19] ibid

[20] Nelson , also surely in McClellan

[21] Caro, Means of Ascent, ch 9, ctrl+f Luis Salas and read forward for the quote.

[22] McClellan pg 83, but I’m switching to ebook.

[23] McClellan chapter 4, ctrl+f Abe Fortas, he only shows up a couple times.