Dear reader, my intention with this substack is to produce in public a coherent book on petrohistory, but what you’re getting here is far from the fully realized work. To support this project, buy a paid subscription now, and I’ll send you a “free” copy of the book in a few years, when it’s ready. It will be better than the below.

Tangent One: Daddy Wallace-Wells

Some would disagree on this point. Ahead of COP27, there was an effort by The New York Times, bylined by David Wallace-Wells, to spin the most recent UN Emissions Gap Report as a victory for “astonishing declines in the price of renewables, a truly global political mobilization, a clearer picture of the energy future and serious policy focus from world leaders” because the report points to a rise of 2.4-2.6 C by 2100. The free market’s done it again, folks. The claim is galling, even insulting.

The Emissions Gap Report does not exist to predict warming. Rather, it uses established baselines to quantify the gap between nations’ voluntary emission reduction goals and their actual emissions. That gap continues to be large, but since the global economy slowed down in 2020 (and is about to slow down again), it wasn’t as bad as was predicted. But unlike the more thorough full IPCC reports, the Gap Emissions Report makes no effort to capture the potential impact of positive feedback loops like natural methane emissions, loss of albedo, and slowing of ocean currents. Given the wild uncertainty that accompanies destabilizing positive feedback loops, there’s not a prediction in the world that’s worth much.

Fuck it, let’s call it now: we’re past the tipping point. If we’re not yet, we will be soon: that much is undeniable. We’ve got unmeasurable methane seeping through the skin of a melting earth. Which means that although human combustion of energy was the instigating input into the system that caused it to lose its homeostasis and cascade into catastrophe, we are no longer the determinative input; there’s nothing we can (or will) do to restabilize the climate.

Tangent Two: The Rule of Capture

The oil industry is intimately familiar with reform movements and over time has evolved the flexibility to absorb and redeploy any of a huge range of ideologies to its own advantage.

The archetype was the campaign against the Rule of Capture, which set the tone for oil-related environmentalism for ever on. It was the conflict between the opposing poles that ended up synthesizing into the major coherent force that went on to dominate the American Century: the wildcatters versus the Majors. From its beginnings in Petrolia to the Second World War, the oil industry was split between the individualist, evangelical, egotistical wildcatters against the always-extant corporate class of Atlanticist liberals. The Rule of Capture was a tenant of the Evangelical strain of capitalism that rose from the South along with oil cash, promoted by guys who were never comfortable letting Standard Oil run their affairs. Importantly, they were also racists.

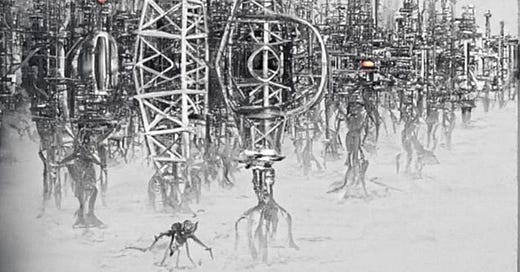

Today recognizable as the “I Drink Your Milkshake” legal regime, the Rule of Capture treated oil the same way that English common law treated hunting game; if it was harvested on your property, it was yours. So if you found an oilfield, you had to race to get all the juice out of it before the neighbors sold their plot to someone else. Oil prospecting under the Rule of Capture was a high-risk suckers game, encouraging manic visions of infinite wealth and deeply apocalyptic religious visions. It created characters like Dad Joiner, who hustled for his whole life, ended deep in debt in his seventies, and then stumbled on the largest oilfield to date, in Rusk County, Texas, and then got swindled out of any profits by H. L. Hunt. Each oilfield had its particular Daniel Plainview historical moment, first at Petrolia in Pennsylvania, Spindletop, East Texas, Oklahoma, all the way up to the Barnett and Bakken.

The Rule of Capture was fun, but it flooded markets with every subsequent discovery. Made it impossible for everyone to make money. Pathological gamblers, the wildcatters were. Thought they were gonna get rich, and then got stuck owning barrels and barrels of worthless sludge that they couldn’t sell to the over-subscribed refineries, and with no storage facilities to speak of. Not only was the Rule of Capture economically ruinous, it was an ecological catastrophe—which exactly no one cared about—but worse, it left oil in the ground, unreachable by the existing technologies. Nothing pissed off the abstemious, mathematical avatars of Rockefeller more than a dollar they couldn’t make.

The problem was one of underground pressure. I used to think that oil actually had to be pumped up from the ground—actually sucked up the hole, like the milkshake. But the early technology all depended on the gas and the rock pushing down on the oil to create a pressurized reservoir that could then squirt out of the ground. Gushers. Of course. The oilmen need to maintain that underground pressure, which is limited. It was usually the lack of pressure, rather than a deficit of oil, that caused an oilfield or a single well to “dry up.” If you stick a bunch of holes in the reservoir at once, the pressure crashes prematurely and oil is left in the ground: money left on the table.

This was considered to be a dreadful, unconscionable waste of potential money by the arch liberal Capitalists. If they could own the oil below the ground, own a share of the reserve, that would be much more orderly for them. Unitization, it is called. If you could own the oil while it was still underground, then if someone came along, bought the plot next to yours and set up a pumpjack, they’d be stealing from you.

Rockefeller sycophants were kept up at night worried about it. Henry “Harry” Doherty, who owned “a number of companies,” made it his life’s mission to campaign in the oil industry to adopt unitization, and failed against the wall of popular support for the Rule of Capture. He took his failure hard, writing in 1929, “I often wish to God I had never gone into the oil business and more often I wish I had never tried to bring about reforms in the oil business.”

Unitization requires government intervention and regulation, which was unthinkable before the War, and a fact of life after the War. Unitization was made the industry standard without fanfare by 1946 as the cartel oilmen gained influence in the War Machine. The wildcatters had been brought into line. Thesis, antithesis. From then on, the interests of the Texan Nexus and the Atlantic Complex were firmly aligned. Synthesis.

Tangent Three: The Real Life Q

I couldn’t verify the claim that James Lovelock was “the real-life Q from James Bond” beyond the Sunday Times article that asserted it. Lovelock did work for the MI5 for most of his career, especially during the Cold War, when that really meant something. Definitely a spook. But Q-for-Quartermaster? Unclear.

James Bond was MI6, not MI5. MI6 claims that the “Real Life Q” was a woman, but doesn’t name her. Q was barely featured in the Ian Fleming novels and first appeared in the movies in From Russia With Love in 1963, when Lovelock was, according to the official bios, working for NASA, looking for life on mars. Q was played by Desmond Llewelyn in all Bond movies until Llewelyn’s death in 1999. So are we to understand that Llewelyn or the screenwriter of From Russia with Love was a big Gaia fan avant la’ lettre? At the time, Lovelock was more associated with the search for exobiology than spycraft, but maybe someone working on the most explicitly anti-Soviet early Bond film knew something that I don’t.

Lovelock did invent things, most notably the mass spectrometer, used to analyze atmospheric components, which he developed at NASA. That’s hardly a car with missile launchers, but close enough, I guess, for hagiography. Obviously the real James Lovelock would have had no problem putting missile launchers on cars if it meant he could kill more Communists. Or, at least, that’s the logical implication of this rumor, the spirit of which I wholeheartedly believe.

Tangent Five: A Sampling of Nauseating Hagiographies of James Lovelock

The Independent 2005

Rolling Stone 2007

Book by John and Mary Gribbin 2009

The Sunday Times 2009

New York 2019

The New Statesman 2019

Noema 2020

The Guardian 2020

The Sunday Times 2022

The Conversation 2022

The Guardian 2022