Dear reader, my intention with this substack is to produce a coherent book on petrohistory, but what you’re getting here is far from the fully realized work. To support this project, buy a paid subscription now, and I’ll send you a “free” copy of the book in a few years, when it’s ready. It will be better than the below.

I thought that this essay on plastic would make a good second read-aloud. It was before I came to Snuckstack, so I don’t know if people have looked at it.

This time I got fancy with audio mixing — this is my first time playing with audacity or recording audio, so forgive me my amateurism. There was this weird impulse to try to bring you into my brain-space.

Last we left off, our historical protagonist, petroleum, was starting up the cold war. I thought that to begin the last half of the 20th Century, I could pivot to plastic as a downstream spawn of petroleum. I was wrong: although plastic is much more visible to us, the main story of environmental history remains the burning of fossil fuels, the suicidal drive to self-immolation, release of energy, and then atmospheric freedom.

Plastic is a mere byproduct of that need for combustion. You’ve got to refine petroleum to make fuel, and you’ve got to get rid of whatever’s refined out. It’s industrial waste that they’ve found a way turn a profit on, no matter how cheaply they sell it. A defecation of the oil refinery.

The biochemicals in petroleum that were entangled while they were buried for millions of years together, forming the muck we call crude oil, are refined apart into different products, but they remain aspects of the same project of petroleum: “moving the Earth’s body toward the Tellurian Omega — the utter degradation of the Earth as a Whole” (Cyclonopedia, 17). They are equal and opposite petrological drives: fuel is consumed immediately, plastic lives forever, and they both are world-destroyers.

Plastic invaded material life utterly and became a cornerstone of the ideology human exceptionalism that is necessary to justify the degradation of the ecosphere. It is infinite in its potential to realize human fantasy: material doesn’t have to look like itself anymore. Here we have a thing that would never exist but for industrial chemistry. What gets lost in this plastic utopianism, on both the consumerist and environmentalist side, is plastic’s origins in petroleum. The oil — infected as it may be with war machines — becomes organized on a molecular level. Does this make the war machines inert, as if trapped in amber? Or do they gain significance and influence? If so, they are masters of camouflage, to appear to be mere subjects of human desire. But that is precisely how they reproduce.

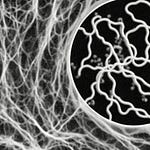

Plastic is unique in that it can never be returned to the earth; everything else can be returned to the biosphere eventually, even at the molecular level — dust to dust — but a synthetic polymer will never break down, will never be metabolized. It is free from, and excluded from, the biological processes that were formerly only transcended by nirvana. A fish may eat it, but it will never become fish. Anywhere it does break down into small enough bits to be ingested (“microplastics”), it will act as a toxic invader, cause cancers and digestive problems, and stubbornly remain itself. Plastic is petroleum made immortal.

Plastic is a core substance to the ideology of petrocapitalism: the visible end of the ideological spectrum. An omnipresent physical reminder that we are not animals anymore (according to the ideology. Out here in reality, of course, we are very much animals). The idea that anything can be artificial or synthetic is itself engineered to make us feel special about ourselves. To make us feel like we alone can instantiate something new into the universe: a substance that didn’t evolve along with everything else here on this planet, Something New Under the Sun. The cost of this hubris is, of course, ultimately borne by the inhuman. And so the mythos of a Synthetic substance come alive, a coming synthetic world, straight into the stupid Singularity. Stupid or not, the fact that plastics will be on this planet forever does, by itself, offer some promise of a post-human epoch on this planet. Perhaps something will evolve that eats plastic, maybe evolve out of the plastic-eating microbes we’ve already released into the ecosphere.

Polymer describes the structure of a molecule: a long chain, comprised of component “monomers.” These molecules are huge; one plastics worker described a polypropylene molecule as a “cathedral that goes on for miles and miles.” Polymers are quite common in nature; DNA is also a polymer.

In an essay about how plastic is alive, it might seem pseudoscientific to point out that DNA is a polymer. But that doesn’t change the fact that the components of plastic and DNA have a basically similar molecular architecture. In the case of plastic, chemists insert different precursor molecules onto the chain to change the physical attributes of the final material. DNA does the same thing, but with much more complexity. Nonetheless, even with simple molecules, over time impressive things can happen once chemicals begin to engineer (or be engineered for) their own reproduction.

Plastic doesn’t reproduce sexually; it has a much more efficient process: reproduction by symbiosis with humans. This turns out to be much faster, more efficient, and more fecund than old fashioned sex. Simply by appearing to be a material, it has colonized every niche of economic activity and every micro-ecosystem. The endless variation of polymer structure, able to become a huge range of different end products, makes it infinitely adaptable. And instead of relying on random mutations for evolution, it uses human engineering, which in turn allows us to feel as if we are gods.

Does plastic have to be formally “alive” to be recognized as an invasive species? Plastic has enabled levels of consumption exponentially higher than any other time before. The endless variation in polymer structures allows it to be endlessly and rapidly adaptable, which is rewarded with massive material proliferation. And, it may be needless to reiterate, it will outlast us.

Just as industrialization had a coal-driven phase and a petroleum-driven second phase, so did plastics. The first plastics, which dominated before and during World War II, were derived from coal ash and tar. After the War, the industry largely shifted to petrochemicals. The plastics made from coal products were largely thermosets, which means they can’t be melted, while today thermoplastics are more common; they can be melted. It was in that moment of transition from one to the other, plastic invaded and quickly dominated our material lives and became fundamental to the ideology of petrocapitalism. That moment climaxed in 1952, when Du Pont and ICC (in Britain) lost control of the formula for polyethylene in an antitrust judgement.

Besides their material differences, thermosets and thermoplastics have different cultural and political resonances, identified with their distinct historical contexts. The dominant feature of early plasticity in the reign of the thermosets was strength. That gospel of synthetic strength reached its climax in and after World War II, and Pynchon does a virtuosic job of making fun of it in Gravity’s Rainbow. Ten years after the war, when polyethylene became the first mass thermoplastic, the key aspect of plasticity became disposability. Strength or durability is an attribute of the material itself, but disposability is an attribute imposed from outside by economic need filtered through ideology.

It’s worth briefly going back to thermosettical times, if only to see what’s changed and what’s stayed the same in our thermoplastic world.

Kraft, Standfestigkeit, Weiße

From the beginning, plastic was declared immortal by the marketing guys supporting the Bakelite brand, which was the first mass-market synthetic polymer. (Celluloid came first, but celluloid, made from cotton, is an antebellum story, and I’m restraining myself from writing about it). The name Bakelite has nothing to do with its bakeability ( you shouldn’t put plastic in the oven, though it won’t melt). It was named after its inventor and chief egotist Leo Baekeland. It entered the market in 1907, and it’s made of coal tar and formaldehyde.

In 1924, the company’s publicity guy hired a freelance writer named John Mumford to write a book about it. He boasted that Bakelite has “a solidity that mocks at the disintegrating forces of heat and cold, time and tide, acid and solvent; with a dielectric strength which fits it to withstand high voltage.” The chemists weren’t looking for a cheap substance, they were looking for a strong one that wouldn’t degrade. Mumford’s book, Story of Bakelite, starts:

Why did we want it that badly? Because,

Plastic and fuel are intertwined not only in their common origin, but in their functions. Electrification would have been impossible without the simultaneous development of plastics. The day of crying need: to combust fossil fuels for power. The need to have power. Certainly aligned with our desires, but can we really take all of the credit for it? It was already “outgrowing its master” in 1924.

Just as plastic was essential to “confine” electricity, so was it able to set the terms for the internet, to define the space of digital disposability and abundance.

One thing that’s hard not to notice about Mumford’s text is that he speaks of both electricity and plastic in an active way that implies that the material has intentionality: “Bakelite, though it had no name then, had been playing ‘face-tag’ and ‘blind-man’s bluff’ with chemists for fifty years.” This is echoed in a 1947 article by journalist Ruth Carson in Colliers magazine: “You feel, when you go into a chemical plant where plastics are made, that maybe man has something quite unruly by the tail.” The material had not yet become inert in public consciousness. It hadn’t yet been fully assimilated into the realm of the human, the way it is today.

As previously discussed, Standard Oil and IG Farben set up a shell company (also a Shell (Royal Dutch) company) in Germany to trade patents related to polymers and their raw materials. This worldwide conspiracy of polymers was satirized heavily in Gravity’s Rainbow. Pynchon gives the back-story to plastic in purely nonfiction terms on page 249 of Gravity’s Rainbow:

This was the same Carothers, Wallace Carothers, who died two weeks before du Pont filed a tranche of patent applications that included one for a chemical called Cadaverine, which could be gathered from the runoff of decaying human corpses, giving rise to the rumor that Carothers had really, ahem, thrown himself into his work. Although Cadaverine could be had more cheaply from coal tar, du Pont’s PR department didn’t do anything to dissuade the public of this misconception, because du Pont didn’t have a PR department, because President Lammont du Pont didn’t give a shit about what the public thought of his company, nor did he need to. Nonetheless, the Cadaverine rumor was eventually squelched by the plastics ideology machines. Kraft, Standfestigkeit, Weiße.

(Dr. Jamf, the archscientist in Gravity’s Rainbow, whose name stands for Jive-Ass Motherfucker because the book loves a dumb joke, doesn’t have a direct historical analog but the chemist Hermann Staudinger was a virtuoso of polymers; in 1933, Martin Heidigger, out to cleanse the Nazi party of ideological impurity, very publicly and angrily denounced him for being a pacifist in World War I.)

The Invention of Disposability

In terms of locating plastic in postwar culture, there is no other place to go — you know it, you want it:

“I got one word for you, kid: plastics. There’s a great future in plastics. Think about it? Will you think about it?”

1963, The Graduate came out. The only memorable line in Dustin Hoffman’s career, and it was said to him by the d-list actor Walter Brooke in his most famous role, Mr. Maguire. It resonated because the main character’s refusal of plastic was the only indication whatsoever in the whole movie that he was trying to free himself from the advantages of peak-prosperity American Capitalism. Because why would you want to, in 1963? Communism had been erased from America twenty years before, the no-alternative world was shaping up in Cold War paranoia, and the economy was surging ahead, exponential growth every year, fueled by…fuel. And so, Mr. Maguire, yes, let’s think about plastics.

Remember that du Pont lost control of polyethylene in a 1952 antitrust suit. This was government working as it should: unleashing an avalanche of garbage onto our heads. This is the moment when Plastic loses its narrative history and becomes a diffuse and omnipresent substance that saturates everything, because that caused the price of polyethylene to fall from the forty cents to ten cents, and lower, per pound. At the time, the price of the ethylene monomer at the refinery’s spigot was less than two cents a pound, and before the IP to make polyethylene was widely available, a lot of it was just getting flared off or dumped into the river. (There’s an apocryphal story of J. D. Rockefeller himself visiting a refinery, seeing the flare, and ordering his minions to find something profitable to do with the ethane.)

The key utility of plastic was not to the consumer, but to the owners of oil refineries, who got to move these byproducts into the “profit” column. Ethlyne and other precursor chemicals continued to be cheap forever; it was less than two cents a pound in 1952, and it’s .19 cents a pound in 2020. Because with 4–13% of a barrel of oil made of these chemicals, you’re always going to have people looking to unload it on the market. Sheer volume is the only way to make a profit in the business. Plastic’s compatibility with that endless, 24/7 flow of petroleum was absolutely dependent on its disposability; for millions of pounds to be made, millions of pounds had to be disposed. It was never a question whose job it was to dispose of it; always the public, assumed to be a municipal service that could later be privatized profitably at the public’s expense. In fact, it soon became necessary to ship out our plastic waste to dump, ahem, “recycle” in poorer countries.

And so the plastic industry paid the culture-makers at Madison Avenue to invent disposability, which is an utterly colonialist idea. Lloyd Stouffer, awarded “packaging man of the year” said at an industry conference in 1956, “the future of plastics is in the trash can.” Reflecting in 1963 on his own prophetic words, addressing his beloved “packaging industry,” Stouffer continued, “You are filling the trash cans, the rubbish dumps, and the incinerators with literally billions of plastics bottles, plastics jugs, plastics tubes, blisters and skin packs, plastics bags and films and sheet packages — and now, even plastics cans. The happy day has arrived when nobody any longer considers the plastics package too good to throw away.” It is difficult to imagine the euphoria of a man getting so rich so easily. Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate was very dumb not to get in on this.

It is true that there was initially some resistance to disposability. There’s a true story of a riot at a public water fountain when the communal tin cup was removed. More to the point, the plastics salesmen had been marketing their product as an indestructible, high quality material, and they were not happy at being told to contradict themselves to their accounts. Maybe Mr. Maguire complained it to his wife at night, maybe he missed a few sales targets.

But overall the public took to disposable plastic products like flies on shit. The ad-men easily linked convenience with disposability, and thereby linked disposable products to first-wave feminism — liberating women by reducing household drudgery, a familiar story.

Disposability was uniquely compatible with the American colonial mindset founded upon infinite expansion. Indeed, probably the only reason the idea didn’t take hold earlier was material limitations — no matter how many resources we stole from native peoples, there’s no stream of material in this world quite like plastic in its bottomlessness.

But that doesn’t mean that the rise of disposability was inevitable. As opposed to strength or durability, disposability isn’t a feature of the material itself, just a change in how we use it. However, disposability is a feature inherent in the flow of petroleum through our industrial processes. Along with the sheer quantity of energy that petroleum presented to humans in exchange for its liberation from the earth into the atmosphere, it came with all of its byproducts. With the adoption of disposability, we adapted to petroleum byproducts, rather than adapting them to our ends. We molded ourselves, our lives, our habits, around the inevitability of cheap ethane and other petrochemicals. ‘The consumer’ was instantiated as a category as a polyethylene sink. Just as the oceans and the wetlands absorb pollution, so do we. And we pay for the privilege.

But we’re not a permanent waste sink; we can buy the plastic, but we can’t store it long-term. That job remains with the land and, to a lesser extent, oceans.

3. Virgin Nurdles

There was an “environmentalist” movement, but that proved to be (or was designed to be?) a weak idea. It wrongly separates humans from the problem. While non-human things are affected by environmental degradation, it’s natural for humans to mostly care about themselves. An effort to get us to care about something outside of ourselves — and at our expense, at that — was doomed from the beginning. That doesn’t mean we’re ideologically powerless against total plastication; now we correctly call it plastic colonialism, and so place it within the scope of human exploitation.

The first little crusade of environmentalism in re: plastic was of course litter. As long as the plastic was put in its proper place, it was fine. That Proper Place is the landfill: the goal is to contain all the plastic on a certain piece of land. Max points out that this assumes a theoretically infinite supply of land — a trash manifest destiny, and practically, a huge amount of the land that is appropriated for landfills are on native territories and sited near communities of color. And once it is covered in dirt, there it stays. Forever, or at least five billion years until the sun engulfs the earth. That time and place — four billion years from now, with still a billion years left — will exist, it will take place, regardless of whether anything is there to witness it. And so will exist all of the plastic.

Following littering, the plastic companies found a more effective message: recycling. I am sure that you already know that plastic recycling is an idea without any reflection in material reality: a scam, not to make money directly, but to keep the oil flowing. Back at the peak of recycling, when China was accepting it, the most that has ever made it into the recycling process was 10% of all plastic waste. We now know that the oil and chemical industries paid for the whole PR push behind recycling that we’ve all been subject to. So all the plastic ends up in the same place, the landfill, whether or not it’s been reduced reused or recycled.

The plastic guys lucked out by associating their version of “recycling” with the re-use of other, real, materials like aluminum and glass. Recycling aluminum and glass and other metals is a real industry with real finances. But plastic recycling was always just a performance. Because you can melt down metal and glass into a relatively homogenous mixture. Not so with plastic, which isn’t consistent with itself at all. Each piece of plastic in your recycling bin is unique — you know this, they put lying little numbers on the bottom of everything made of plastic, so that you would think it was recyclable. It can be sorted in to types and melted down, but the resin degrades every time you do that. Most of the recycled plastic products you see for sale look like melted-together balls. Virgin nurdles, the raw form in which thermoplastics are sold to manufacturers, on the other hand, are completely cheap.

The popular discourse around plastic requires me here to take a detour into the ocean. Because this is what we hear the most about these days: ocean plastics. In fact, this framing of a real ecological crisis is a cover to obscure the real problem, the fishing industry. At least half of the plastic in the oceans is from discarded fishing gear, like nets. Also, that half does the most damage, because it’s specifically designed to kill fish and ocean animals indiscriminately. So remember that the next time you’re snipping a six-pack ring, imagining the turtle that won’t get caught in it. Also, much of the rest of the plastic in the oceans is PRE-consumer waste, in other words, industrial waste. Max Liberion, again, has found Nurdles on remote beaches in the Canadian north Atlantic.

It turns out that this pollution directly from plastics factories has a long and venerable history, and that liberal environmentalists have a long complicity in it.

In March 1972, Edward J. Carpenter of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute announced publicly that he had found tiny bits of plastic in Long Island Sound at a density of one to twenty samples per cubic yard of water. He suggested that toxic plasticizers were being released into the marine food chain, and that plastic provided surfaces for bacterial growth and blocked digestive tracts of smaller fish. The next month, he quietly told the President of the Plastics Industry Association, Ralph L. Harding, Jr., that the plastics he was referring do were fresh spheres of polystyrene resin (nurdles), which indicated dumping by a plastics processor. Carpenter told Harding that when he released his report to the public, he hoped to also report, “that we have had the cooperation of the plastics industry in locating the source” of the industrial dumping. Harding sent a letter to his members and the culprit came forward and agreed to end the dumping in exchange for anonymity and non-prosecution.

And that’s where it stands today: Non-prosecution.